A History of the Michigan Central Station

2405 W. Vernor Highway, Detroit, Michigan 48216

The Michigan Central Station is within the general vicinity of the West Side Detroit Polish American Historical Society’s official boundaries and is one of west side Detroit Polonia’s historically significant sites. Situated at 2405 W. Vernor Highway between 14th and 16th Streets, the station, also known as the depot, is located approximately one-half mile to the east of Interstate I-96 and on the south side of Michigan Avenue. It is extremely significant to the Society’s history because of its close proximity to Detroit’s Polish American neighborhoods. At one time, its owners employed a large number of Polish Americans, who worked there in office positions or as laborers.

The Michigan Central Station also shares roots with Detroit’s automobile industry and has a particular connection to Henry Ford and the Ford Motor Company.

The depot was built to replace the previous Michigan Central Station in downtown Detroit, which burned in a fire on December 26, 1913. The original station was located on a spur line, and while convenient for freight service, its location made it inconvenient for the numerous passengers requiring service in the area. The depot, which was built for the Michigan Central Railroad, placed passenger service on the main line. It was formally dedicated on January 14, 1914, and remained in operation until January 6, 1988, when Amtrak began services at the location.

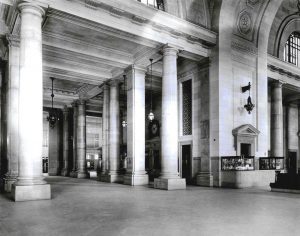

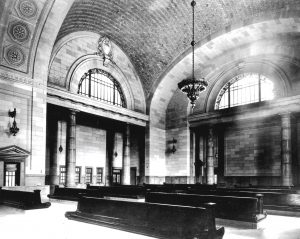

The Michigan Central Station was designed by the Warren & Wetmore and Reed and Stem firms, who designed New York City’s Grand Central Terminal. The depot was designed in a Beaux-Arts style of architecture, which draws upon features of French neo-classicism and which style was taught at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, primarily during the period from the 1830s through the 19th century. The style also contained elements of the Renaissance and Baroque styles. This style was extremely prominent prior to the French Revolution and evolved from the French classicism of Style Louis XIV and the French neoclassicism of Style Louis XV and Louis XVI.

Some characteristics of Beaux-Arts architecture are a “flat roof; rusticated and raised first story; hierarchy of spaces, from ‘noble spaces’—grand entrances and staircases—to utilitarian ones; arched windows; arched and pedimented doors, classical details: references to a synthesis of historicist styles and a tendency to eclecticism; fluency in a number of ‘manners’; symmetry; statuary; sculpture (bas-relief panels, figural sculptures, sculptural groups), murals, mosaics, and other artwork, all coordinated in theme to assert the identity of the building; classical architectural details: balustrades, pilasters, festoons, cartouches, acroteria, with a prominent display of richly detailed clasps (agrafes), brackets and supporting consoles); and subtle polychromy.” 1/

These Beaux-Arts architectural features are undoubtedly what make the Michigan Central Station one of the most arresting and captivating structures in the City of Detroit. Roosevelt Park, which was completed in 1920, serves as the depot’s front lawn and is an impressive gateway. The 500,000-square-foot depot was built at a cost of $15 million. It consisted of the train station and an office tower with 18 stories. Originally, the plans included a hotel, which was to be housed within the upper floors of the tower, but the hotel was never incorporated. The Michigan Central Railroad and subsequent owners of the building used the upper floors for offices, which was their original intent, although the top floors were never fully furnished.

The depot’s main floor boasts gorgeous marble walls and high, vaulted ceilings. The large waiting area on the main level was designed to resemble an ancient Roman bathhouse. A large hall housed the ticket office and arcade shops and featured Doric columns. The concourse, built with brick walls, was highlighted with a large copper skylight. A ramp led from this level, which took passengers toward a tunnel that led to the train platforms, which could be accessed by either stairs or an elevator. Passengers were served from 10 passenger platforms consisting of one side platform and five island platforms along 10 paired tracks. One track served the Railway Express Agency (REA) mail service, and there were seven additional freight tracks. A large baggage area and a mail handling section was located below the tracks, along with offices.

Streetcars were the primary mode of transportation in Detroit and other major cities during the early 1900s. By the late 1800s, electric rail systems had made their debut, with nearly 900 electric street railways having been built in the United States by 1895. A major advantage of the electric streetcar over horse-drawn streetcars was the elimination of having to clean up after the horses’ waste. Train passengers arrived at the Michigan Central Station via local streetcars or interurban trams or railcars that operated between cities.

But another major revolution was taking place during the early 1900s, especially in Detroit. Entrepreneurs were building factories that produced a new contraption called the automobile. The Detroit Automobile Company, founded on August 5, 1899, was the first. It had 12 investors, including Henry Ford and Detroit Mayor William Maybury. The company lasted only about 17 months and was dissolved in January of 1901—a lesson to anyone who might be tempted to give in to despair and to abandon their dreams after a setback.

The Detroit Automobile Company was located at 1343 Cass Avenue and Amsterdam in Detroit’s downtown area. Capital investment in the company was $15,000, or approximately $574,000 in 2025. Henry Ford ran the company without pay until he left his position at Detroit Edison. He took a nominal salary afterwards with the goal of making his company profitable like the one that produced the Curved Dash Oldsmobile, which was being built at a plant operated by Samuel Smith. In retrospect, Ford would later believe that he focused too much on profits at the expense of innovation.

On November 20, 1901, the Detroit Automobile Company was reorganized into the Henry Ford Company and later became the Cadillac Automobile Company on August 22, 1902, after Ford departed. Henry M. Leland, an engineer with Leland & Faulconer Manufacturing Company, continued to run Cadillac, which was named after Antoine Laumet de La Mothe Cadillac, the French explorer who had founded Detroit in 1701.

The Cadillac Automobile Company merged with Leland & Faulconer Manufacturing in 1905 and formed the Cadillac Motor Company. On July 29, 1909, Cadillac was purchased by the General Motors Corporation.

Leland would later quit Cadillac and form the Lincoln Motor Company at 6200 W. Warren Avenue on Detroit’s west side to build Liberty engines during World War I. During the post-World War I recession, Henry Ford purchased the Lincoln Motor Company on February 4, 1922, and turned it into a luxury automobile manufacturing plant for his Lincoln vehicle brand, which would compete with GM’s Cadillac.

In 1903, at the age of 36, Henry Ford launched his Ford Motor Company from a converted factory on Mack Avenue in Detroit with cash from 12 investors, including Horace Dodge, who would go on to found the Dodge Brothers Motor Vehicle Company. Ford moved the Mack Avenue operations to his Piquette Avenue factory in Detroit and then to the now-famous Highland Park Model T plant on Manchester Street at the corner of Woodward Avenue. The plant revolutionized not only automobile manufacturing, but also the world. With its automated assembly line, by 1924, the plant produced approximately 5,400 automobiles per day, and approximately 2.1 million Model T vehicles per year.

Ford, Dodge, Oldsmobile, and Cadillac are just a few of the numerous automobile manufacturers that make up Detroit’s early history. By 1915, there were at least 48 car manufacturers and 100 suppliers in Detroit, several of them in the southwest area. That number had grown dramatically from 1902. When the Michigan Central Station was completed in 1914, passengers arriving from downtown Detroit arrived by streetcar or interurban service. Originally, there were plans to connect the station to the Cultural Center via a wide boulevard, but the plans never materialized. Still, the station continued to thrive for decades.

The New York Central Railroad acquired the Michigan Central and operated in Michigan from 1915 to 1968, when New York Central merged with the Pennsylvania Railroad and created Penn Central Company. Subsequent railroads that operated from the depot included the Ohio Railroad and the Canadian Pacific Railway.

Rail travel was at its peak in the United States at the beginning of World War I. At that time, more than 200 trains departed from the depot daily, and passenger lines extended all the way from the main entrance to the trains’ boarding gates. The other major train station serving Detroit was the Fort Street Union Depot. By the 1940s, the Michigan Central Station served more than 4,000 passengers daily, and more than 3,000 employees worked in the office tower. Among those arriving at the depot included Presidents Herbert Hoover, Harry S. Truman and Franklin D. Roosevelt, actor Charlie Chaplin, inventor Thomas Edison, and artists Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera.

One of the depot’s shortcomings was that a large parking area had not been contemplated in the original design plans. Thus, when automobile use became a primary mode of transportation, the site lacked the necessary parking space for passengers’ vehicles.

In the 1920s, Henry Ford began purchasing property within the depot’s vicinity and had plans to pursue development in the area. However, the Great Depression and other circumstances prevented him from following through as intended.

Military troops traveled extensively by train during World War II and used the depot during that time period. But after the War, the trend shifted more toward the automobile for both leisure and other use. Train travel tapered off so much that by 1956, the New York Central sought to sell the depot for $5 million, one-third of its $15 million construction price. In 1963, there was another attempted sale, which yielded no interested purchasers.

Provisions had to be significantly reduced. By 1960, the New York Central had ended its direct service south to Toledo, which was picked up by the B&O. In 1963, the B&O relocated its trains to the Fort Street Union Depot. The last New York Central train headed northbound for Bay City departed from the depot in 1964. The joint New York Central/Central Pacific trains were discontinued, and the Canadian Pacific Trains to Windsor were terminated in 1967. By the end of 1967, the New York Central had ceased operating its named trains.

Sadly, that same year, the cost of maintaining the depot was deemed untenable. No longer able to sustain operations, the restaurant, arcade shops, and the main entrance were all closed, in addition to the main waiting area. All that remained open were two ticket windows, which serviced passengers and visitors alike, who shared the parking lot entrance used by railroad employees working in the building. The only remaining New York Central trains that ran were segmented operations between major cities. The New York Central’s successor, Penn Central, took over the segmented operations in 1968.

In 1971, Amtrak, whose official name is the National Passenger Rail Corporation, was founded to operate many U.S. passenger rail routes. In 1975, Amtrak reopened the Michigan Central Station’s main waiting room and entrance. A short time later, Conrail, formally the Consolidated Rail Corporation, moved its Detroit operations into the depot. These two rail companies breathed a short-lived new life into the dilapidated building.

Conrail was the primary Class I railroad in the Northeastern U.S. between 1976 and 1977. Class I railroads are the largest rail carriers in the U.S., and they own the majority of tracks. Conrail operated until 1999, when large portions of it were split up between Norfolk Southern and CSX. It was created by the federal government to take over the potentially profitable lines of multiple bankrupt railroad carriers, including Penn Central Transportation Company and the Erie Lackawanna Railway. When Conrail began operations in the Michigan Central Station, numerous employees from Penn Central were transplanted in Detroit. A large number of them were Polish Americans.

In the late 1970s, I began working for Conrail as a court stenographer. I was one of five employees who held the position of court stenographer, or court reporter, at Conrail’s Detroit location in the Michigan Central Station. Our job was to record the proceedings of official hearings that were required by the federal government when there was a railroad accident or injury, and then prepare transcripts, certify them, and mail them to the federal government in Washington, D.C., within the required time period.

Conrail recruited court reporters from the Elsa Cooper School in downtown Detroit, and I was recommended by one of my instructors there. I attended court reporting classes at night after working in my position in International Banking at Manufacturer’s Bank in Detroit’s newly built Renaissance Center. At the time, the Elsa Cooper School was considered by some to be Detroit’s preeminent court reporting school.

Back then, only the first through fifth floors of the depot were occupied by Conrail, and the floors above the fifth floor were unoccupied and had no glass in the window frames. Conrail and Amtrak were the only companies that occupied the building. Employees could hear the wind howling through the open window casings on a windy day. From outside, looking up, as we approached the building, we could see shreds of the old, yellow, tattered window shades lapping out through the window casings like long tongues.

The depot was a stark contrast to the Renaissance Center, where I worked for the Vice President of International Banking in a brand new office. Banking—and in particular, International Banking—were considered highly prestigious, and employees were required to adhere to a strict dress code. I wore skirt suits, often three-piece with matching vests, long-sleeved blouses that tied at the neck with puffy bows, sheer nylon stockings, and high heeled leather pumps. My hair was cut short and professionally styled. Because I had attended college and had planned to continue with my education, I had been approached by the Executive Vice President and offered a career with the bank, which I declined. My boss was shocked when I decided to leave the bank and work for the railroad in the decaying Michigan Central Station, where everything was much more casual.

At times, as I walked through the deserted building, I could envision people from other eras walking through it, sitting at the lunch counter or standing at the old passenger gates, looking just like they must have appeared in the 1920s, ‘30s, or ‘40s, frozen in time. It was hard to believe that millions of passengers had once passed through the beautiful depot.

The once-stately depot had become abandoned, for the most part, except for a handful of Conrail’s management and office staff, who supported administration and the workforce of the surrounding rail yards, including the trainmasters, yardmasters, and foremen. My direct supervisor was Polish, as were several members of the upper- and lower-level staff. Polish names were as abundant as they were in the neighborhoods surrounding the old station.

Vestiges of the old lunch stand remained in the middle of the main level of the depot, long forgotten. It had swivel stools around it that were bolted into the floor, similar to those used along the counters of old soda fountains. As I recall, the old leather seats were red in color. Like the rest of the depot, they were very old and worn at that time, their leather coverings shredded like the window shades. There was still an old menu with prices on the wall above the lunch stand, as though someone were going to return from the past and order a sandwich.

I worked on the first floor in Room 142, the Division Superintendent’s Office, which was actually a level up from the entrance that the employees used to access the building. The entrance was located in the back of the building. When we entered, there was a guard booth to the right behind a wall with a bullet proof glass window, where the Conrail Police were stationed for security. To the left was the elevator. It had a manually operated gate operated by the elevator operator, a transplant from the old Penn Central Railroad.

The elevator operator was a slim, jovial African American man. He wore black slacks, a black vest, a white shirt, and a black bowler hat. He was delightfully cheerful and had a charming giggle when he laughed. As I recall, he had been with the railroad since around the 1930s. He pulled the gate across the elevator door and operated the crank to take employees up to their work floors. He had a small stool that he sat on inside the elevator car.

Many immigrants of various nationalities worked for the railroad, a large number of whom had been with the railroad for decades. Some had started working for the railroad when they were 15 or 16 years old. I remember an Italian woman who began working “right off the boat” from Italy when she was 15 years old. She had come to America with her brother when she was very young.

Railroad employees were extremely dedicated and loyal. Another woman in our division, who worked for the superintendent, served the railroad for over 50 years and had never missed a day of work.

A lot of Polish people worked at the railroad because the depot is located in what was once a predominantly Polish neighborhood.

Christmastime at the depot was special. Each year, a giant Christmas tree appeared in the grand arcade of the main level of the station, under the soaring arches. The tree was very tall, around 20 feet high, and it was decorated with old-fashioned colored light bulbs. It was a mystery as to where it came from. It just appeared one day during each Christmas holiday season and was there one morning when we entered the building. Maybe it was erected by Amtrak personnel or by volunteers. It was hauntingly beautiful, just like the depot.

It was fun to go out to lunch in the neighborhood, although we had only a 25-minute lunch break, so we had to call ahead and place our orders. Most days I brought my lunch, but I recall a few lunches at Starlite Restaurant on Michigan Avenue. I also remember getting carry-outs from White Tower Hamburgers. For a quick getaway, I drove to the surrounding stores on Michigan Avenue and walked around for 10 minutes. My favorite pastime was looking around in the old dime store, which may have been Neisner’s. Forty-five years later, I still have a silk scarf that I purchased at the store for 50 cents.

One of my cherished memories of working in the depot is seeing the 14th floor. There was an old maintenance man who was probably in his seventies at the time. He knew that I had an affinity for the depot and that I was a historian. One hot summer afternoon, when things were a bit slow, he asked my supervisor if he could show me the 14th floor. I had no idea what was about to transpire.

As the elevator door opened, I was speechless. The entire floor was filled with artifacts from Penn Central Railroad. Antique desks, chairs, and leaded glass-doored bookcases were stashed from corner to corner, wall to wall. Cabinets, tables, and furnishings from railroad executives’ offices of decades past were hidden away as if stowed in an abandoned summer home. There were cast iron floor lamps with tattered, yellowing shades and boxes of brittle documents strewn everywhere. Old railroad journals and log sheets that had been bound in leather volumes lined the floors. It didn’t appear that there had been any effort made to document any of the items that had been deposited there.

The sun’s rays shone down through the empty window casings and produced a hazy glow that enveloped us. I felt as though I had been given a glimpse into another era and transported to a world long forgotten. It was a reverential moment that nearly brought me to my knees.

When the Elsa Cooper School closed, I transferred to the Macomb Academy of Court Reporting in Mt. Clemens and made the drive four nights a week after work to complete my training and certification as an official court reporter. My goal was to work in the courts. When the American railroad industry was deregulated by the Staggers Rail Act of 1980, there was upheaval within Conrail, and it was time for me to move on. I left not long afterwards to begin my career in the courts, and a few years later moved on, completing my education and serving the legal profession in the automotive industry. But to this day, working for Conrail in the Michigan Central Station continues to be the most memorable period of my working career.

For decades, Polish Americans from the depot’s surrounding neighborhoods worked at Michigan Central Station. One such employee was a lady named Frances (Kaczmarek) Walczak (January 20, 1924 – December 27, 2013). Frances was the mother of Society member Richard H. Walczak (March 11, 1944 – September 4, 2021), and she worked at the Michigan Central Station for 37 years, retiring in 1985. She held many positions, primarily cleaning person elevator operator.

Frances and Henry Walczak were married on April 25, 1942, in the basement of St. Andrew Catholic Church on Detroit’s west side. They lived with Frances’ parents at 7339 Sarena, between Chopin and Tarnow, where they raised their family and where Henry slowly rebuilt the entire house while working as a tool and die maker, in woodworking, and as a handyman.

Frances began working at the Michigan Central Station as a cleaning person with a group of other Polish American women, cleaning the office spaces on the floors above the terminal. Most of the time, she worked the second shift, from 4 p.m. to 12 a.m. The floors were mostly wooden, and the women had to scrub them clean. It was hard work. She also operated a very heavy, industrial-strength vacuum cleaner.

Later, Frances worked as an elevator operator. In a story provided to the Society, Richard recalled accompanying her to work periodically as a child, when he observed her operating the elevator. He recalled the lever that had to be pushed forward and backward to stop the car. That was a task that required much skill in order to get the elevator car to stop precisely at floor level to ensure that no one tripped while getting on or off.

In the late 1970s and 1980s, Conrail was losing money, and like other businesses, it began to downsize and terminate low-seniority employees. Frances exercised her rights and was able to bump other lower seniority employees out of their positions in order to hold onto her job. She assumed positions that were not traditionally held by women at that time, such as baggage handler. She counted and inventoried freight cars in the rail yards at various locations around Michigan and served as a driver to engineers, shuffling them back and forth between trains and the depot. She did whatever she was asked to do, performing her duties to the best of her ability in order to avoid retiring early. She was able to hold onto her job until her retirement in 1985.

Conrail eventually became profitable in the 1980s after federal regulations had been lifted by the 4R Act (the Railroad Revitalization and Regulatory Reform Act of 1976) and the Staggers Act of 1980.

In 1978, Amtrak had begun a $1.25 million renovation project. In 1984, the Michigan Central Station was sold for a transportation center project, but it never materialized.

On January 6, 1988, the depot was closed, and the last Amtrak train departed from the station on that date. Amtrak service continued at a nearby platform on Rose Street until the new Detroit station opened in Detroit’s New Center area in 1994.

In 1996, the station was acquired by Controlled Terminals Inc., the sister company of the Detroit International Bridge Co., which owns the Ambassador Bridge. Both companies are part of a group of transportation-related companies which were owned by late businessman Manuel Maroun, Chairman and CEO of Centra Inc., which made changes to the tracks and platforms.

There were plans in 2008 by the station owners to renovate the depot at a cost of approximately $80 million. However, money was not the only issue; determining the right use for the structure proved to be the greater problem.

Under Detroit Mayor Kwame Kilpatrick’s leadership, demolition of the depot was considered in 2009, but a lawsuit ensued under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, and the depot was spared.

The depot’s missing windows had for years been a major issue. Due in part to the missing windows, water had been pouring into the building for decades, causing major damage. In 2015, the owners announced plans to replace more than 1,000 windows above the first level. In late April of that year, the City entered into a land swap deal with the Bridge Company, under which, in addition to the land swap, the City would receive up to $5 million for park improvements. In addition, the Bridge Company agreed to replace the windows in the train station. This was achieved by December of 2015.

By 2016, the owners had invested approximately $12 million toward renovating the building. This included the window replacement, installing electricity, rehabilitating the damaged roof, cleaning out the flooded basement, reinstalling the elevator, and revitalization. A “Detroit Homecoming” event was held in the station in September of 2017, the first legal event to be held at the depot since its closure in 1988.

It was shortly afterwards, on March 20, 2018, when the Detroit News published an article stating that the Ford Motor Company had entered into discussions about purchasing the depot. This news was met with boundless enthusiasm by Detroiters, those in the surrounding areas, and even worldwide. On May 22, 2018, ownership of the Michigan Central Station was officially transferred from the Moroun-owned MCS Crown Land Development Co. LLC to New Investment Properties I LLC. On June 11, 2018, the Moroun family confirmed that Ford was the new owner of the building. The depot’s story was beginning to come full circle.

Ford purchased the station along with the Roosevelt Warehouse and planned to use the building as a hub for its autonomous vehicle development and deployment and as an anchor for the company’s Corktown campus. It was proposed that the building would house both Ford offices and the offices of suppliers and partner companies. Restaurants and retail were planned for the first floor concourse, and housing was to be created on the top floors.

For the first time since the depot’s closure in 1988, Ford reopened the building with a grand community celebration on June 19, 2018. Local rapper Big Sean performed, and it was announced that Ford had plans to renovate the station, as well as the adjacent warehouse, within four years, or by 2022. The company’s $1 billion capital improvements project also included the creation of a development on the west side of Dearborn and renovation of Ford’s main headquarters in Dearborn. Ford sought at least $250 million in tax and other incentives for the project.

Quinn Evans Architects of Detroit was hired to manage the renovation of Michigan Central Station. Phase I of the immense project began in December of 2018 and involved drying out the building and reinforcing the structural columns and archways.

Phase II began in May of 2019 and consisted of masonry restoration of the tower and concourse, retiling of the ceiling of the waiting room, and repair of the structural steel. Because so much of the building’s architectural details had been lost over the years to exposure to the elements and to vandalism, 3-D scanning technology was used to recreate them.

In total, more than 3,100 skilled trades artisans labored on the building’s renovation and devoted 1.7 million hours toward its completion.

The depot has always held a sense of mystique and enchantment, and during the renovation process, it drew people together in a new and invigorating way. During the late 1980s and 1990s, it had become an invitation to vandals and looters, who pillaged many of its treasured fixtures. Ford’s announced purchase and renovation plans drew forth many from the shadows who had seized souvenirs from the building and who wanted to return them in order to make the depot whole again. Some lights and the main clock were recreated using 3-D technology.

In 2021, work began to restore the building’s masonry façade. But the COVID-19 pandemic delayed the planned completion date of 2022.

In January of 2024, Ford announced that it was seeking approval for a zoning change that would allow for the development of a hotel to be added to the top two or three floors of the depot.

Some elements of the dormant years, such as a wall of colorful graffiti, were left intact and artistically preserved by the renovators. This was intended to preserve every era of the depot’s history with accuracy.

At last, the long-awaited public reopening occurred on June 6, 2024. Tickets to the grand opening free concert featuring a lineup of Detroit performers sold out within five minutes. William Clay Ford Jr., Executive Chairman of the Ford Motor Company, spoke about fulfilling a dream of returning transportation to where it had originated—in Detroit—and of the sense of renewal that the project represented. Joshua Sirefman, CEO of Michigan Central Station, spoke of the new life that Detroiters had instilled in the depot and of the enthusiasm that stretched far beyond the depot and Detroit.

Concert headliners included the legendary Diana Ross, Big Sean, Jack White, and Eminem.

An open house continued from June 7 through June 16, prior to commercial tenants relocating to the building, which was planned for the fall of 2024. It was anticipated that more than 60,000 people would tour the station between those dates. Modified open house hours were scheduled beginning on June 21. No tickets were required for the open house tours.

As of 2024, the former train shed area was being redeveloped into a public park. Discussions have taken place between Amtrak and VIA Rail Canada regarding the feasibility of connecting one Chicago-Detroit train to a Windsor-Toronto round trip. As of April 2025, it is unknown whether or when this might take place.

In many ways, the Michigan Central Station is the most quintessential icon of Detroit. It stands like a beacon, symbolizing the hope that has always represented Detroit and which is summarized in Detroit’s motto: “Speramus meliora; resurget cineribus,” meaning, “We hope for better things,” and, “It will rise from the ashes.” This motto was penned by Father Gabriel Richard after a fire ravaged Detroit on June 11, 1805. With no professional fire department to battle the blaze, Detroiters banded together to form a human chain and doused the flames with buckets of water that they carried from the river.

There is something peculiar and extraordinary about the Michigan Central Station. Its singular, quiet, timeless beauty is particularly symbolic of Detroit’s west side Polish Americans who once inhabited the surrounding neighborhoods and worked within its vicinity. It represents their resilient, determined spirit and the fortitude they brought to the neighborhoods into which they poured so much of themselves.

Sources:

- 1/ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beaux-Arts_architecture

- Gomulka, Laurie A. “A History of the Lincoln Motor Company.” In West Side Detroit Polish American Society e-Newsletter. Vol. 104, August 2024, Pp. 8 – 11.

- Gomulka, Laurie A. “Was Grandma a Feminist?” In West Side Detroit Polish American Historical Society e-Newsletter. Vol. 103, June 2024, P. 17.

- https://detroitmi.gov/departments/detroit-parks-recreation/parks-and-greenways/roosevelt-park

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amtrak

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beaux-Arts_architecture

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cadillac

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conrail

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Detroit_Automobile_Company

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ford_Motor_Company

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Michigan_Central_Station

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Streetcars_in_North_America

- https://michigancentral.com/michigan-central-station-celebrates-detroit-and-its-historic-reopening-with-concert-seen-around-the-world/

- https://www.motorcities.org/southwest-detroit-auto-heritage-guide/early-auto-boom

- Walczak, Richard H. “Memories of My Parents: Frances (Kaczmarek) and Henry Walczak and Detroit’s West Side.” In West Side Detroit Polish American Historical Society e-Newsletter. Vol. 43, August 2014, Pp. 6 – 8.

Photos:

- Michigan Central Station exterior with Canadian Pacific, 1927

- Michigan Central Station exterior with cars parked under archway, 1913

- Michigan Central Station arcade with archways, ca. 1916

- Michigan Central Station main floor waiting area showing large marble columns, 1916

- Michigan Central Station empty waiting area with benches and chandelier, ca. 1916

- Michigan Central Station view of entrance to train tracks, ca. 1916

- Michigan Central Station newsstand, ca. 1914

- Michigan Central Station passengers waiting at gate, ca. 1945

- [Above, all WSDPAHS archives]

- Laurie A. Gomulka, Division Superintendent’s Office, Conrail, Michigan Central Station, December 1979. Collection of Laurie A. Gomulka

- Christmas tree in the Michigan Central Station, Christmas season 1979. Photo source: Laurie A. Gomulka. Collection of Laurie A. Gomulka

- The newly renovated Michigan Central Station, lit up at night, June 2024. Photo source: https://e-architect.com/wp-

content/uploads/2024/06/ michigan-central-station- detroit-building-lighting- b070624-j.jpg - Photos of the Michigan Central Station not specifically credited in the body of this text are from the WSDPAHS archives and are reprints of original photos from the archives of the Library of Congress.